Inspiration: Damnation

Béla Tarr, Damnation, 1988.

Home Viewing

It wasn’t very long ago that if one wanted to see films notable for their distinctly experimental nature and relative historical import, one had to:

a. attend screenings in major metropolitan areas;

b. rent prints oneself from The Filmmakers’Coop or Canyon Cinema, mostly, though New Yorker Films had an extensive catalog of European art cinema, and still might;

c. wait for a nearby university to host a screening.

There were occasionally other options but not often. When I first became interested in alternative cinemas 1, home video was still largely the province of mainstream work, though not entirely. One could find, here in New York anyway, films by Beth B. & Scott B., R. Kern, Vivenne Dick, Maya Deren, Kenneth Anger, and Mark Rappaport, for example, but the dearth of experimental work from 1960-1980 or so was, to me, remarkable 2 Because much of the work in question concerned itself with the physical properties of filmstock, it was frequently excluded from video release at the outset. Seems an archaic distinction these days but this was the 20th, not the 21st, century.

Public viewing has characterized nearly all film-viewing for most of its history. At the least, one invited friends, colleagues, or family to see one’s films, and in any case it has been unusual, until the last 30 years or so, to discuss a film without having viewed it in the company of other viewers. Which means, or meant, that unless one made a concerted effort to escape the screening venue in silent solitude, one was likely to end up talking to someone else from the screening for some period of time, however brief. Opinion or study was, under these circumstances, born of a combination of etiquette, remark, debate, and consensus. It was social.

As for myself, I’ve had the By Brakhage: An Anthology, Volume 1 since its initial release and have never watched it alone. Though I pre-ordered A Hollis Frampton Odyssey the day it was announced, I have yet to view a single frame of it: I’m waiting until I can find a time that mutually suits my friends, that we might watch some of the films and discuss them together in person.

Alternative was an adjective then, not a genre, and I pluralize cinema because my interest led me to many different kinds of filmmaking from many different times and places; like most of my friends at that time, it was important to see everything.↩

That the work of these filmmakers has yet to appear on DVD or online streaming is a mystery to me, as is the current lack of L.A. Rebellion cinema, though that is a topic for another time.↩

From My Old Blog, September, 2006: My Favorite Book and Its Author

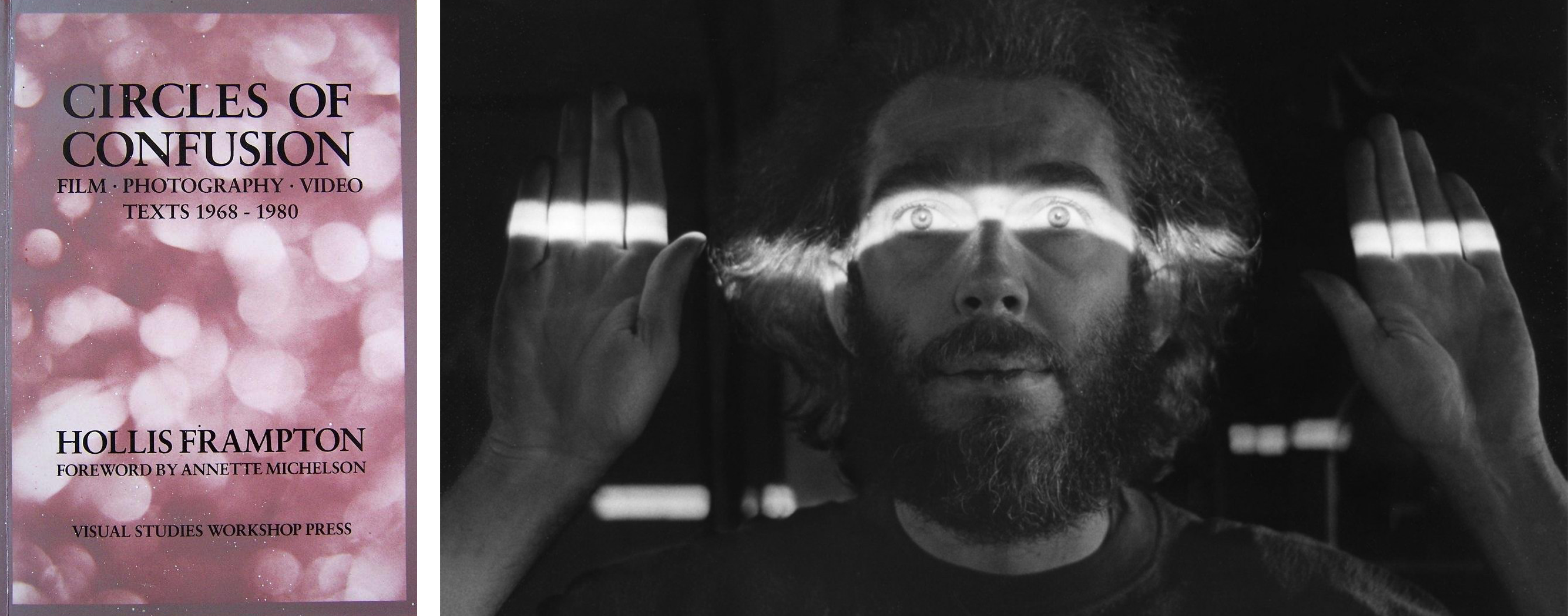

On the left is a book called Circles of Confusion: Film · Photography · Video: Texts 1968-1980 that was written by the man on the right who was (in his lifetime, from 1936 until 1984) and is called Hollis Frampton. It is a book of essays, most of which were originally published in Artforum magazine when it was edited by Annette Michelson, a film theorist and critic whose abundant and energetic wing fostered three generations of scholars and filmmakers, including and perhaps especially, Hollis Frampton.

Visual Studies Workshop Press in Rochester, NY, published the collection. The connection between VSW, Rochester, and Frampton is not as obscure as it might seem: Frampton taught at SUNY Buffalo in the 1970s, the campus of which is situated roughly 70 miles west of Rochester, home of Kodak, and therefore a center of film manufacturing.

Such connections are, rudimentarily speaking, the stuff of Frampton’s thought and work. He came to still photography via Ezra Pound and James Joyce; to filmmaking via still photography, painting, and a devotion to mathematics and science; to video and photocopiers via filmmaking and a return to still photography.

His films run the gamut from his earliest efforts whose concern was primarily motion (e.g. Manual of Arms, 1966) to found-footage films (e.g. Maxwell’s Demon, 1968) to so-called structural 1 works (e.g. Lemon, 1969; in this case a full-frame shot of a lemon subjected to a range of light and exposure, about which Frampton said, “As a voluptuous lemon is devoured by the same light that reveals it, its image passes from the spatial rhetoric of illusion into the spatial grammar of the graphic arts.”) to the unfinished Magellan, which was intended to expand to include a film for each day of a 371 day cycle. A spirit of inquiry, a sense of humor, and a feeling for the necessity of art infuse his writing as they do his films. These are curious works, works of a curious mind, works for curious minds.

I’m not sure I agree with the entirety of this page’s explanation but it does serve to provide a definition of this kind of filmmaking. I prefer to view structural film, like film noir, as a style or method as opposed to a genre.↩

All This to Post a Link: Slow Movies

It’s a defense I rarely have the patience to make anymore, that of so-called slow movies, which are, of course, only slow relative to to current movie-pace conventions, whatever era’s taste might be represented in a given movie.

I think it’s worth noting, however, that slow movies are not necessarily long.1 When I first got into film, the chief examples of slow-movies were largely limited to European pictures from the 1970s. My personal choices for best-of-the-genre 2 are probably still Wim Wender’s Kings of the Road (1976, 175 minutes) and Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975, 201 minutes), both long movies by any measure.

Suffice it to say that from one vantage, these are movies in which nothing happens, yet from another point of view they are movies in which the characters’ stakes are simply measured in smaller increments than mainstream fare.

Sometimes, as in the case of Kelly Reichardt’s middle pictures, we only learn what we need to about the characters to get us effectively through the scenario at hand: a kind of awkward effort to reconnect in Old Joy and a desperate couple of days (and the inevitably of reliance on other people) in Wendy and Lucy. Movies of such provision are frequently short by industry standards, preferring to dwell on their scenes rather than hustle viewers on to the next one.

Another current filmmaker who eschews contemporary pacing is Andrew Bujalski, whose directorial work3 takes a privileged look at a largely privileged class of young adults, hipsters, and students. It is not Mr. Bujalski’s aim to make boring movies but he does aim to make movies about boring people, or people made boring by their selfishness and self-consciousness.

For my part, I determined several years ago that:

- Falling asleep during a movie doesn’t mean I’m bored. It means I’m tired. I don’t sleep when I’m bored, I smoke cigarettes (though I also smoke when I’m not bored).4 I would rather doze off during a movie that tries something new than remain alert throughout a movie that doesn’t.

- By and large, I enjoy movies that challenge accepted practice on any level more than those that don’t.

- Exceptional movies are exceptional for all kinds of reasons. Unexeceptional movies are usually unexceptional for the same reasons.

- I prefer filmmakers that presume their audience to be a community, if only by virtue of the fact that all of its members will have seen their film(s).

All of which is to say that I don’t care if mainstream audiences ever like slow movies. My heart goes out to critics and reviewers who still feel the need to defend these films: Films – In Defense of Slow and Boring – NYTimes.com (Via Alex Ross.)

Kelly Reichardt’s work, known for its real-time event structure, breaks down as follows: *River of Grass, 1994*, 100 minutes; *Old Joy*, 2006, 76 minutes; *Wendy and Lucy*, 2008, 80 minutes; *Meek’s Cutoff*, 2010, 104 minutes. The oldest and most recent of Ms. Reichardt’s films, which I have not yet seen, are the two that are of conventional feature-length. I’ll guess that compared to the middle two, both of which are favorites of mine, *River of Grass* and *Meek’s Cutoff* unfold like Jason Bourne or Harry Potter pictures, and therefore require the extended duration. If I’m wrong about this, no matter.↩

We could call it the Real-Time Domestic genre, allowing that “domestic” describes wherever the characters hang their hat(s), a location that might well be nowhere in particular. Other directors whose work fits or has fit into this genre are, off the top of my head, Roberto Rossellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, Jean-Luc Godard, Margurite Duras, Robert Altman, Yvonne Rainer, Takeshi Kitano, Tsai-Ming Liang, Horikazu Kore-Eda. There are dozens of others from all parts of the world and the entire history of cinema.↩

*Funny Ha Ha*, 2002, 85 minutes; *Mutual Appreciation*, 2005, 109 minutes; *Beeswax*, 2009, 100 minutes.↩

I haven’t smoked a cigarette since January 2015. — Z. February, 2023.↩

Symmetry

Courtesy of my pal, Gurldoggie.

Todd Meredith Taylor

from ben mcfall on Vimeo.

An astonishing solo performance, captured by my friend Ben McFall. Many thanks, B.