Upcoming Jawbox Shows

This is a friendly reminder that we’re playing here in New York City at Le Poisson Rouge on July 20-22 and then in D.C. at The Black Cat on July 23. You can click on the venue links for tickets and info. The NYC shows are kind of survey of our catalog, each night emphasizing a certain era of our time together. We’re not playing complete albums but we did pull out a bunch of stuff just for these shows. Here’s a clip from a recent rehearsal to whet your whistle.

We also recorded some new versions of two songs from our first album and a Wire cover. You can buy them via Bandcamp.

I hope you enjoy it all and look forward to seeing you next week.

Day’s Plays Guest Post: Matt LeMay

[You can learn more about Matt here and here.]

They Might Be Giants, Flood (1990): Like many children of the 1990s, I enjoyed listening to “Particle Man” and “Istanbul (Not Constantinople)” way back when. But revisiting the album now, I can’t get over what a gloriously improbable and incoherent hodgepodge the whole thing is. This record has two gratuitous trumpet solos, one and a half sea shanties, a country-power-pop song that name drops the dB’s and the Young Fresh Fellows, an opening chorale announcing the album’s release… it shouldn’t make any sense, and it doesn’t make any sense, but it makes its own kind of vaguely sense-like thing and I love it. The song “Dead”, an off-kilter ditty about boredom, reincarnation, and groceries that apparently lifted its vocal interplay from the Proclaimers’“I’m Gonna Be (500 Miles)”, has become a private anthem for the darker moments of this strange time: “Now it’s over, I’m dead, and I haven’t done anything that I want / Or I’m still alive and there’s nothing I want to do.”

Absent City, Continue Normal Living (2020): The title kinda says it all; this record was intended to be a balm, and it is a balm, and it is just so lovely and comforting without being naive or heavy-handed. It’s a real tightrope act to make a record that feels needed and relevant in these times without self-consciously winking and nodding to “in these times”. I’ve been appreciating this record the same way I appreciate the plants in our living room, which I think/hope registers as the King Lear-style reverse-backhanded compliment it is intended to be. Start with “California Afternoons” and keep going.

Miss Eaves, How It Is (2020): This EP makes me miss New York, makes me miss my friends, and makes me wish that the early 2000s “Electroclash” moment had been less self-conscious, more inclusive, and more fun. I had the pleasure of mixing a track that Miss Eaves made with my friend Casey Dienel four years ago, and it’s been amazing to watch both of them become even stronger, funnier, and more fearless artists since then. The song “Stacks” captures the sandwich-and-not-much-else-rich life of a NYC freelancer better than anything else I’ve ever heard, and specifically makes me nostalgic for the varied and plentiful sandwiches at Hana Food in Williamsburg.

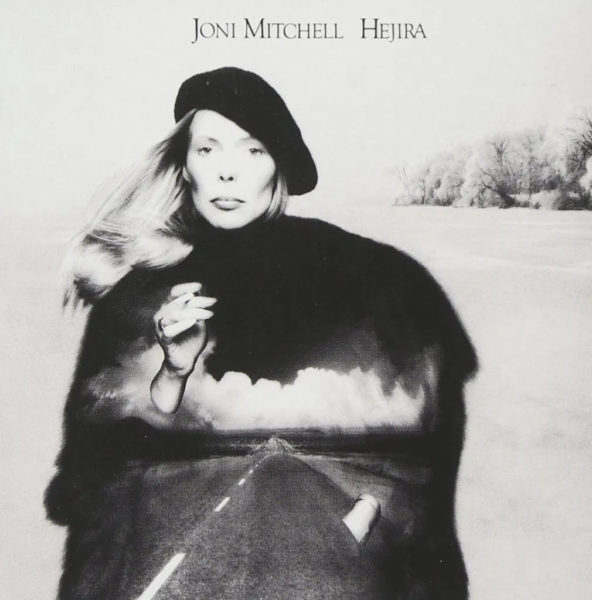

Joni Mitchell, Hejira (1976): I started digging into this album in earnest earlier this year, and “Amelia” has been haunting me ever since. The song is built around a circular chord progression that modulates up and back without ever settling into anything that feels predictably like a verse or a chorus. It’s a mind-blower when you stop and think about it, but it never asks you to stop and think about it–it just works its magic, subtly, invisibly. I don’t think there’s a higher achievement in popular music than that. We spent all of 2018 living in a house off a dirt road in New Mexico, and this album sounds like the color of the sky and movement of the planes flying overhead and I don’t really know how else to describe it.

Cynthia Gooding, The Queen of Hearts: Early English Folksongs Sung By Cynthia Gooding (1955): Cynthia Gooding was a friend of my father’s family, an unsung pioneer of the American folk music movement in the 1950s and 1960s, and the owner of a strong and singular voice that I wish more people had the opportunity to hear. I grew up hearing these songs as performed by my father, but I never had a recording of them until I tracked this album down on Discogs. Most days, I’m not prepared for the emotional timewarp that this album triggers–but some days, it’s exactly what I need.

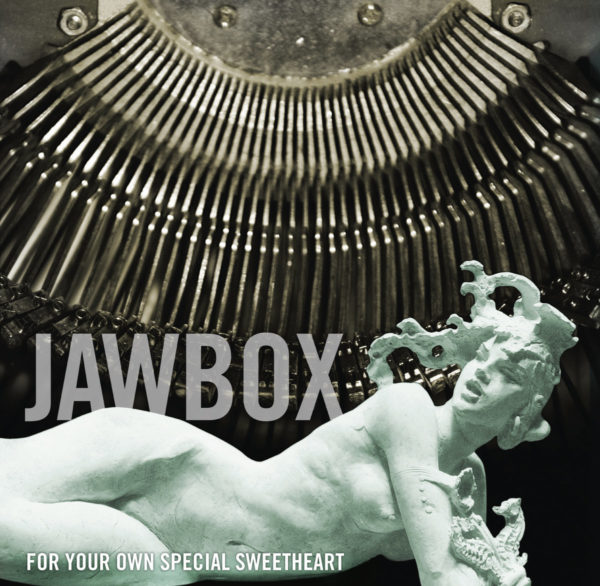

Jawbox: For Your Own Special Sweetheart (1994): One way I’ve been keeping (relatively) stable and (relatively) healthy this time is to practice drumming as often as I can. I’ve played drums since I was 15–first in an awful high school band with hated pharma exec Martin Shkreli and then in an excellent band called Lame Drivers with my dear friend and Get Him Eat Him bandmate Jason Sigal–but I didn’t own a drumset until we moved to New Mexico in 2017. Since then, I’ve maintained a “drum practice” playlist with a mix of old(er) and new(er) songs. A handful of songs from this record have been mainstays on that playlist, and have served as informal markers of progress; first, I could comfortably play “68”, then “Savory”, and now, slowly but surely, “Motorist”. It’s amazing to feel my brain, hands, and feet talking to each other in new ways–so let me close this out by expressing my gratitude to Zach, Scott Plouf, Devin Ocampo, Dan Didier, Chris Wilson, Orestes Morfin, and every other musician whose work has kept me going, both mentally and physically, during this [insert string of adjectives here] time.

End of the Night, Philadelphia, PA

From my old blog, February, 2007: On Selling Out, Sort Of

My experience as an artist is more or less divided into two spheres: on the one hand, I’m a musician, a practice which has always involved public performance and the explicit realization of a community. On the other hand, I’m a poet, a practice which has been, until the last year or so, an almost entirely private practice, one I shared with a handful of people, whose publication was limited to a couple of poems published several years ago (including, as it happens, the same poem twice). By and large, the two spheres remain separate, though, decreasingly so. I have tried to model my life as a poet on what I learned in the Rochester, NY and DC punk scenes from roughly 1989-2000: that artists, regardless of their art, carry with them a responsibility to the world in which they create and exhibit their work (it is, after all, created and exhibited in the same world).

The Jim Saah photograph above is from a Jawbox show at the Black Cat in DC; I think the year was 1994 and it might have even been the show advertised in the poster next to it. I have kept a print of the photograph on my refrigerator since that time to remind me of several things, chief among which has become the best-integrated art/politics scene in which I have been an active member. It was the reason I moved back to the area in 1991, and found it to be an invigorating and inspiring time and place to be as both writer and musician (I had, when I left Rochester, decided to give up music entirely, in favor of literature; thankfully my mind was changed nine months later when I joined Jawbox). There was a near-constant air of protest, of seeking out materials and economies that abandoned convention in favor of defiant humanism and concern for essentially leftist values. This took place mostly among bands and show-attendees, who were gathering anyway for music and new ideas. There were frequent benefit shows, protests, and a network of people around the world whose contact with each other depended on touring bands. The link was inherently political: we were doing our thing, not the mainstream thing. It worked, too.

By 1994, several of us (by which I mean bands) had signed to major labels, in hopes, variously, of reaching larger audiences, or at the very least, having more time and money with which to make records. I think Jawbox was more concerned with writing better songs than we were with fame. The jump to the majors allowed us to practice more, tour more, and record under better circumstances.

The ramifications were obvious enough then as now: we were selling out. For my part — I can’t speak for J., Bill, or Kim — I’ve always thought of it as cashing in, though there wasn’t really much cash and I’m not certain that the distinction even matters anymore. For what it’s worth, I didn’t feel like we were wrecking anything by signing to Atlantic; that is, the decision was ours, the consequences were ours, and it didn’t reflect on any other bands, labels, or fans. I was wrong.

The scene from which we’d come felt, in some circles, betrayed, and the mainstream rarely has the patience required for unconventional art. We were ignored by our label within nine months of our first release and completely pushed aside within a year. Our story is not at all unusual except perhaps for the degree to which we continued to practice a DIY-based method, regardless of being on a major label. We knew what we were getting ourselves into (most of the time). I don’t know that this recounting requires much elaboration at this late date so I’ll just say that if I was in that situation today, I’d probably handle it differently, though this remark is qualified by knowing that the circumstances that made Jawbox possible at all no longer exist for me.

In the end, I can’t say I regret our deal with Atlantic. Kim and Bill even bought our tapes back from the label and are planning to re-release both For Your Own Special Sweetheart and Jawbox online. The fact remains that we made our most challenging music under those conditions, and my experience in that band has positively served my consciousness as much as anything else I’ve done, before or since.