Kimberley sent this to me earlier this evening. I’ve been waiting to stream TANGK until we tear the shrink from the LP but that’s starting to seem like unnecessary depravation. What a wonderful song!

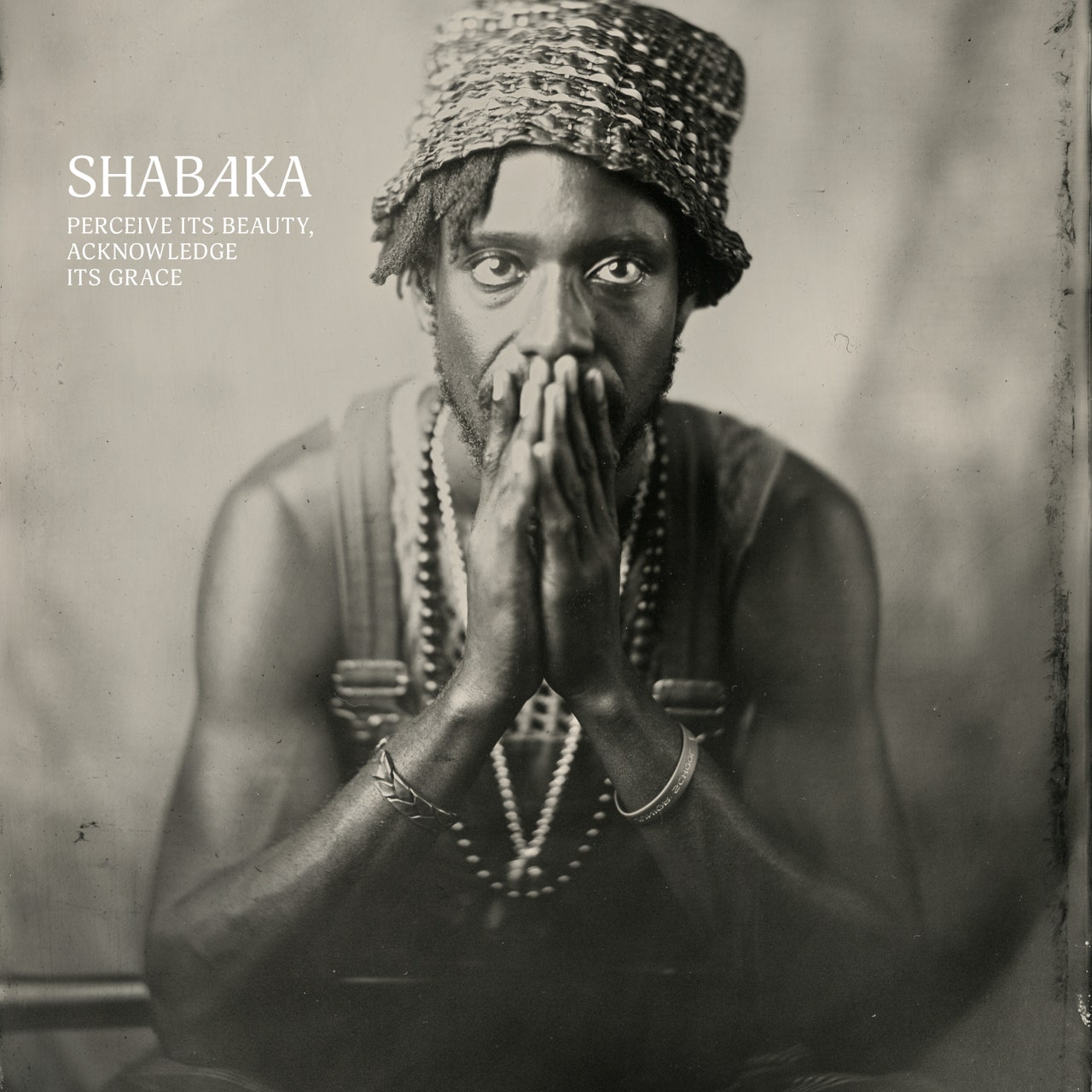

Shabaka

Disappointed to find that Shabaka’s Perceive Its Beauty, Acknowledge Its Grace has been removed from Bandcamp. It’s still worth linking to, however, so you can find it on your preferred streaming platform here.

My Life with Peter Gabriel, Part Five

I joined Jawbox in 1992. It wasn’t my first band but it was my first mature band, the first group that was already on its way, touring, making records. It was not only a new practical level for me but a new social one as well. The band was known and popular. It was a breakout situation for me and I was anxious. My first couple of months with the group were spent learning the songs. Our singer and leader, J. Robbins was touring with his friends in Pegboy and we used the time at home to get me settled in with Kim (Coletta, bass) and Bill (Barbot, guitar and vocals).

I knew the songs as a fan so playing them, learning them, was more a matter of getting a handle on the arrangements than finding my place in them, a goal we postponed until J. got home. By that time, nine weeks later, I was ready to run through the set. Looking back, I established myself quickly, and if memory serves my first show in the band was in July of that year and we left for tour immediately after that.

We wrote, in those short months, two songs as a group, a new and exciting turn for the band. Previously, J. more or less wrote the material and presented it to the band fully formed and arranged. One of the new songs, “Jackpot Plus!” was, in some ways, as much of a straight-up post-hardcore song as we ever played. Like many young players, I was creating my parts to suit the genre as opposed to molding the genre to suit my playing. Two relevant drummers in particular, Peter Moffett from Government Issue and John McEntire from Bastro were on my mind, and though I no doubt failed to rise to their level, I think my beats are a short step away from “Jaded Eyes” and “Recidivist.” What I wanted was to sound like them.

The other song we wrote was called “Motorist.” It was a new kind of song for the band, a new feel. It marked my first effort to rip off Manu Katché, Peter Gabriel’s drummer from So onward. It was, like many such efforts, a failure. I was hoping for something along the lines of “Digging in the Dirt,” which was released the month before on Peter Gabriel’s Us the eagerly anticipated follow-up to So.

There was a lesson in this failure: not sounding like Katché led directly to a reliance on my own voice and feel on the drums. And I noticed it. Whether or not I sounded like anyone else became immaterial and even something to be avoided. That is, I think “Motorist” was the first time I sounded like myself. From that point on, I brought influences I knew I could not reproduce, just to see what would happen in the group.

We re-recorded the song (“Jackpot Plus!,” too) for For Your Own Special Sweetheart and the sort of refinements we were looking for individually and as a group are audible. The production is more focused, more in tune with the kind of energy we sought in our live performances. And the feel of it is shared, common among us. By the time we recorded FYOSS we were functioning much more as a single unit, feeling our performances together instead of playing by rote.

I found that almost anytime I introduced one of Peter Gabriel’s or Manu Katché’s rhythmic strains into the band, it warped or escalated or shifted into a new and original feel. To reiterate at the risk of redundancy, the distinction between influence as a site of imitation and influence as a site of creation changed everything. I don’t think I quite knew this before. And as our music became increasingly reliant on the drumming, these strains came to guide much more of what we were writing. As was true for the band as a whole, this was the moment I transitioned from being a musician who sought to make sounds like those I loved (imitation) to one who sought to make sounds that originated in my own playing (creation). Like PG says in “Sledgehammer,” paraphrased: I shed my skin. This was the new stuff.

My Life with Peter Gabriel, Part Four

I began playing a drum set when I was 10 and showed promise and aptitude for the instrument from the start. It didn’t take long for music to become a significant part of both my identity and my worldview. During an especially unhappy period of time in Fairfax, VA when I was 12-13, drumming and music came to be my only source of social capital or interaction. I was fortunate to find, or be found in shop class by, a similarly disenchanted boy, one of extraordinary musical skill named Kevin who needed a drummer. What 12 year-old approaches another and says he “needs a drummer?” Prior to this he had only spoken to me twice, the first time he said “Cool bandana,” which was of course not true though I believe he thought it was. The second time, looking over my shoulder as I pored over the pages of the fall 1981 Pearl Drums catalog, he pointed at a black five-piece kit and said, “I have that one.” So he needed a drummer. He had my dream drum set and no one to play it while he played keyboards or guitar. I have counted Kevin McKendree among my dearest friends since that time. His talent persists, too: he is among the most intuitive and supportive musicians I have ever known. A true inspiration.

I bring all of this up because it taught me that playing music could be the entirety of a life, or close to it, its whole flow, in and out, as Peter Gabriel has come to say, delivering me from all manner of pain and confusion and loneliness to a world of people working together to make themselves and others feel good or better. And not only did I encounter this sensibility as a player, I came to internalize it as a listener. And a year later, I saw the “Games Without Frontiers” video for the first time. Three years after that, still imbued with this sense of music I could neither quite grasp nor articulate, I heard So for the first time, a record that would change me forever, become a baseline of what music, any music, can aspire to in its ability to self-generate its moment and environment, its own container, its own prophecy and destiny. It was very heavy stuff for my young mind.

I didn’t know this at the time, but it was a sort of big bang in my consciousness. Or if I intuited it, it wasn’t something I could deal with yet. The missing ingredient, as it happened, came in 1988 when I joined or fell into the punk scene.

It turns out that many young punks in the mid- and late-1980’s met because they had gone to rehab. I won’t go into it any further than that, but I was no exception to this trend, even if I seemed to get there (to punk, not to rehab) a few years later than my friends. This was fine, though, as they were there to shepherd me along. I came to understood punk to be much more of a mindset than a style, and it was through this mindset that I recognized the full achievement of So. The link was that one’s commitment to one’s art or even one’s self at all, could be unfettered by what one used to do or be. One could decide to change and, with varying degrees of difficulty, do so. If I wanted to be punk, I’d have to decide what that meant or looked like.

If I wanted to play punk music, the same principle would apply. There was room in the scene to drum in a way that included whatever I brought to the group. It was much more open than I understood other music to be and this sensibility gave rise to the drumming I would develop a few years later when, after a brief hiatus from playing altogether, I joined Jawbox. All of which brings us to my playing on the record for which I am usually best known, For Your Own Special Sweetheart.

My Life with Peter Gabriel, Part Two

From roughly 13-15 my friends and I hung around anywhere we could, in parking lots, diners, parks, driveways, basements, family rooms, derelict train cars, the high school bleachers (but never on game nights). A favored spot, at least to get high, was simply behind the fence at a gas station near our school. Like most such places we claimed — a certain stairwell comes to mind, or a narrow strip of grass next to a bank parking lot — we were oblivious to the surrounding area, babies in an elaborate, public round of peek-a-boo: if we didn’t see the adults, they didn’t see us. It was a fragile scene in those years, trouble at home for some of us, trouble at school, and it seemed like the whole world was trying to keep us at home or school. Although I did my best to steer clear of serious trouble, I found some, mostly in drug use and the eventual self-determined cessation of my public education in the course of my sophomore year. It was a difficult time.

But there were two things in my case that made a difference: I was honest about my truancy, and I never missed my curfew. Why would I lie about skipping school if both the school and my mother knew I had done it? I saw no point, and the penalties for skipping were not, in my estimation, prohibitive. As for the second thing, why would I stay out later than my mother wanted when I could get high and listen to music and read at home? I was perfectly happy, most of the time, to abandon my crew and head home to food and shelter and the safety and comfort of my bedroom. As it happened, mine was a home almost entirely free of conflict, if not worry. There was plenty of worry but my mother and I seemed to agree about it, share the struggle.

And so I came to spend an increasing amount of time alone with either headphones and my stereo or my Walkman.1 This would have been 1984-5, as I recall, and my listening was all over the place: Bob Dylan’s first three records were favorites; metal as it was understood at the time by Kerrang magazine; Jimi Hendrix, especially Axis: Bold As Love; Stevie Ray Vaughan’s Couldn’t Stand the Weather;2 British Invasion, especially the Who and the Kinks. Lots of music. Always music. There was also radio, 96.5 WCMF,3 92 WMJQ,4 and 104 WDKX.5 Radio was social, mostly for the car or seasonal hanging out at people’s homes, speakers in the window or dragged outside. This was the stuff I shared with others. My private music, on the other hand, was Gil Evans-era Miles Davis, especially Sketches of Spain, a reasonable collection of Motown and Chess tapes, and Peter Gabriel, especially Security which for reasons described elsewhere both confirmed and assuaged my most intense fears.

I’m not sure why I kept these musics to myself. I suspect it stemmed from my response to my parents’ divorce, which was to hold things close for fear that they might be taken from me, or that this kind of compartmentalization kept me from being totally abandoned, kept something for myself, gave me a barely-conscious feeling of control. For some kids, divorce leads outward and they seek relief in likeminded and collusive souls whose presence secures them from further pain and separation. Experience is validated by consensus. Some, however, like me, withdraw even from their peers and seek refuge in more private selection and recursion. It’s hard on the kids either way and the difference is more temperamental than qualitative. Without a group’s affirmation, the first kind of kid sinks. Without sufficient fortification, the second kind of kid can’t bridge the gap between themself and the world around them.

Peter Gabriel’s music eventually became my sufficient fortification, the music that first bridged this gap for me.

-

Unrelated: the first tape I ever wore out was a TDK C90 with Judas Priest’s Unleashed in the East on one side and Iron Maiden’s Number of the Beast on the other. At some point while listening to Maiden, Priest’s “Sinner” became audible, backwards. ↩

-

Subsequent editions of this record have replaced the original sequence on most streaming platforms. I link here to the original sequence because it’s the one I’m referring to. ↩

-

“Rochester’s only home of rock and roll!” ↩

-

Somewhat awkwardly, never quite able to rise above the status of Rochester’s other home of rock and roll. But there was plenty of rock and roll to go around back then. ↩

-

A black-owned and operated station since the 70s whose call letters stood and stand for Frederick Douglas, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. ↩

Energies: A Note on Music and Disbeliefs

I do not believe that the act of making music, however deliberate or spontaneous it might be, aspires to a preordained ideal. That is, there is no perfect music, except insofar as a given musical piece or performance fulfills the needs of its participants — listener, composer, and performer alike. This fulfillment is, in the end, all that matters.

I also do not believe that all music aspires to art, nor should it, any more than any other activity aspires to art. I emphasize my use of the word activity because I believe music is something one does.1