Love Call, 1971.

Zach Barocas, Diasporist Diarist

Love Call, 1971.

The Collective, 1989.

There’s an interesting piece in The Atlantic on one of the more compelling aspects of our time, ambivalence about cars. My wife and I own a Prius C, which is about as size- and fuel-conscious as we’re likely to be in our current circumstances here in New York City with no ready, secure access to charging and no desire to drive a newer, bigger car. We use our car mostly for utility and sometimes for convenience. It is, however, not something we think about very much. We have, we use it. We worry about replacing it sometimes and then forget to worry.

But there is no doubt that I bought into the American myth of automobile-derived freedom from an early age, and by the time I had my own car at 17,[footnote]Or more likely when my older friends gained steady access to their own or their parent’s cars, which preceded my own by a couple of years.[/footnote] it was a haven from all manner of perceived and real threat, hassle, and infringement, a site of recklessness, retreat, intimacy, and independence. From ages 15–21 or so, my entire worldview was shaped while leaning against, sitting on, and hanging around in cars of all different makes, models, sizes, and shapes and in all states of repair. Much of the time, it didn’t matter what kind of car we were in as long as the following criteria were met:

Additionally, the etiquette of these rides was fluid but firm:

Review: A Contemporary Music Group’s Next Era Begins | The New York Times

It sounds like there’s a lot going on here. But while undeniably jam-packed and charged with grave themes, the evening progressed with a sense of unhurried equanimity. That was in large part thanks to the figure cut by [Douglas R.] Ewart; when he paced the stage to grab a new instrument, you could hear bells — tucked away in the pockets of his colorful, homemade concert suit — jangling peaceably.

Wisdom of the Elders, 2016.

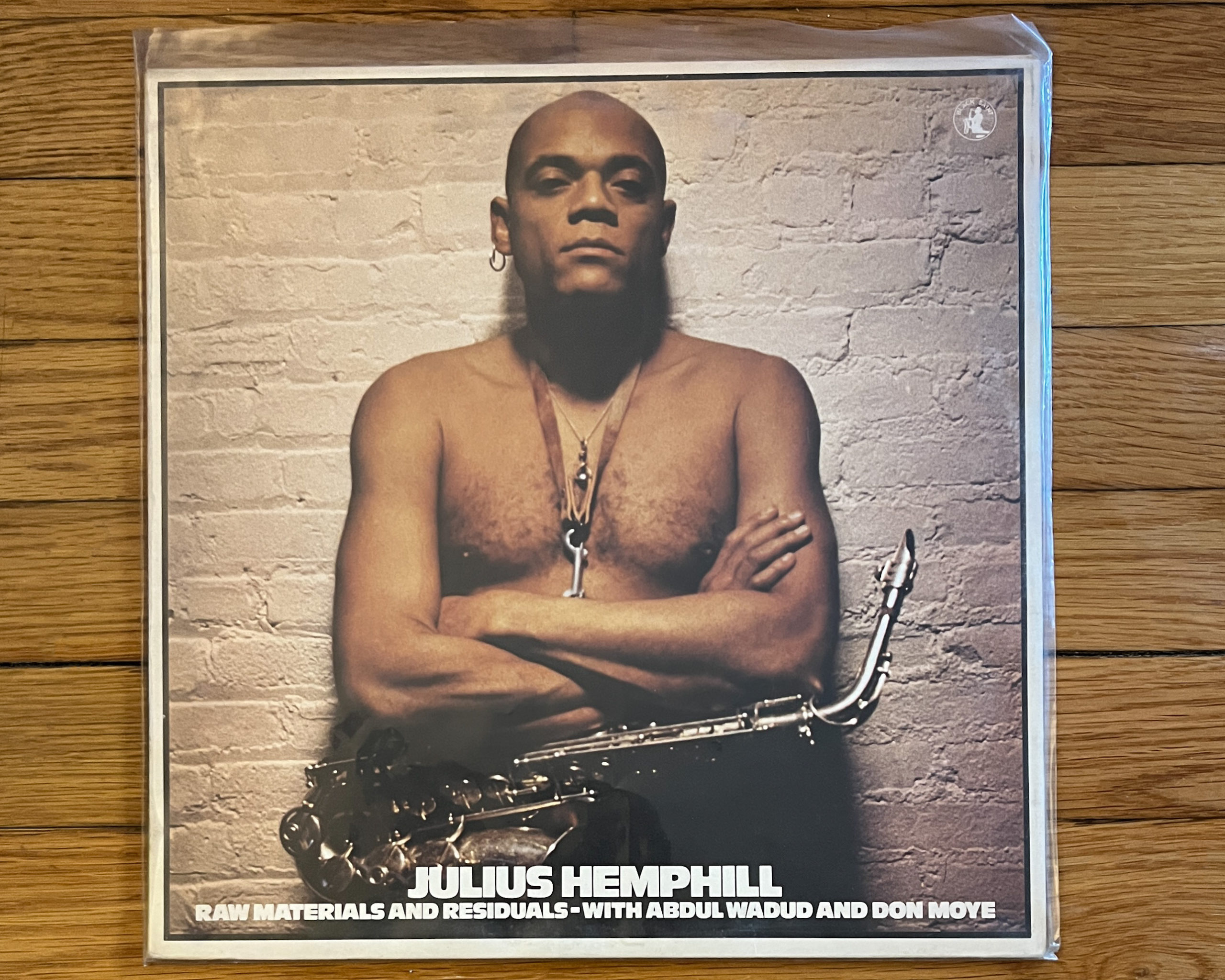

Raw Materials and Residuals, 1978.

Radio By Diane di Prima | The New Yorker

In Hasidic Judaism

it is said that before we

are born an angel

enters the womb,

strikes us on the

mouth

and we forget all

that we knew of

previous lives—

all that we know

of heaven