Mark Strand once said that poets reach maturity when they move from saying private things in a public language to saying public things in a private language.1 I understand this statement to mean that a poet matures into not only a sense of scale wherein his/her work comes to describe more universal things than personal feelings or personal feelings as universal things; but, simultaneously, a style.2

We see this kind of development equally among all artists, I think, and a mark of the maturing, as opposed to fully mature, artist is that his/her work remains a kind of test, a challenge to the audience to decode and interpret his/her effort. Though this might yield some reward for artist and audience, s/he is nearing the state of maturity that will free him/her from the need to obscure his/her subject (frequently with objects) but isn’t quite there. My own maturation as an artist and an audience member has been characterized by impatience with this kind of obscurantism, even when I can parse the clues. One is always hip to some reference or other but it shouldn’t be the full price of the ticket.

For better or worse, I tend to approach most art literally and let it go to work on me from there. My own musical preference for ensemble composing and performing without vocals stems from this condition, as it supports an it-is-what-it-is art, contingent only on what the group plays, not on what the audience might think about what one of us is saying. In this way, my mature practice, such as it is, is marked by collaboration, understanding that what one is trying to get across benefits in every instance from direct involvement with and the ideas of others: the audience collaborates, exhibitors and distributors collaborate, one’s inspiration and aspiration collaborate. One way or another, the art experience is always shared.

That said, art work begins with inspiration and aspiration. One is moved to get something across, an image, a sound, a structure, or whatever else, as Denise Levertov put it, raves to us for release. In my work, what, exactly, do I try to get across? It’s fairly simple: we must be good to each other.

Two examples of the basic philosophy behind this idea take G-d as their object, not their subject. I suspect you’ll catch my drift when you have a look at them.

The first is from James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time,

If the concept of God has any validity or any use, it can only be to make us larger, freer, and more loving. If he can no longer do this then it is time we got rid of Him.

The subject of this statement is our inspiration, aspiration, humility, and selflessness. Its object, on the other hand, is G-d, who we are free to embrace or deny according to our need. This sort of statement, a benevolent subject paired with a provocative treatment of an ideal object typifies certain of Mr Baldwin’s statements, especially as he reached his artistic maturity. During his peak, he was a master of this kind of statement.

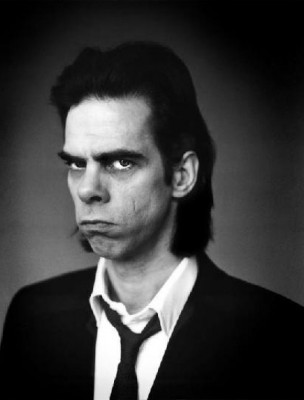

Another example is Nick Cave, who in a lecture he delivered on writing love songs said,

Actualising of God through the medium of the love song remains my prime motivation as an artist. The love song is perhaps the truest and most distinctive human gift for recognising God and a gift that God himself needs.

I won’t make any proclamations about Mr Cave’s faith but I will point out that the role he assigns to G-d is similar to Mr Baldwin’s in that they both invoke G-d’s mutual need for us, as conjurers or gift bearers.3 That they speak of G-d only matters here insofar as he represents an ideal, either an ideal inspiration (Baldwin) or aspiration (Cave). Each man’s use of a mutually held ideal — held, that is between the idealizer and idealized — affirms the necessity of striving or longing and a goal. In other words, the gap between the effort and the object is the subject. The effectiveness of the work is defined by the ability of its audience to recognize and identify with the effort, not the object.

This kind of connection speaks to the variety of music, poetry, or other art that initially captivates us: we respond to the uncommon relation of common reactions to common things.The things in question likely appeal to us specifically at a certain point in time, regarding death, injustice or oppression, a favorite location, a favorite car, or an especially difficult break-up, for instance, but the stuff that stays with us does so even after these events have receded into the past. So one might be struck by a poem that speaks to one’s immediate circumstance but what will keep one interested in the poem is what it tries to do, and as we mature, what it continues to do.

A related idea is the preference for genres. If we cling to the event or time during which we were first captivated by a work, we will seek similar-sounding or similar-looking material to repeat or revive both the original experience and the captivation. This is distinct from the relationship described above in that it asks art to seize an experience rather than develop as we ourselves mature.