Jamie Saft Trio, “Sturiel,” Astaroth: Book of Angels Vol. 1, 2005.

Zach Barocas, Diasporist Diarist

Jamie Saft Trio, “Sturiel,” Astaroth: Book of Angels Vol. 1, 2005.

Max Roach, “Freedom Day,” We Insist! Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite, 1960.

Joe Henderson was the first saxophone player whom I ever called my favorite.1 As a younger man getting publicly into jazz, it seemed that the known heavies among the people I spoke with were more than I could get my ears around.2 There were tenor players I favored, Dexter Gordon chief among them, but I found myself wanting something that leaned into more aggressive improvisations, turned occasionally away from standards, maybe carried a message of personal – if not cultural, political or social – freedom. Sonny Rollins was almost perfect but older guys, like in their 40s, seemed to enjoy him a little too much.

Enter Joe Henderson. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s he found a home at Blue Note and swung with the best of them. 3 In the meantime, however, he was playing some very different kinds of jazz, appearing on most of Andrew Hill’s miraculous LPs from 1963-19654, Pete La Roca’s Basra (1965), and Larry Young’s Unity (1965).

The years 1963-1964 also bore Henderson’s emergence as a leader. In that time he had four records appear under his name5. Frankly, there’s not a klinker to be found on any of those sessions.

So by 1967, if he wasn’t famous among listeners he remained in high demand among other players. One of my favorite saxophone numbers of all time comes from this period.

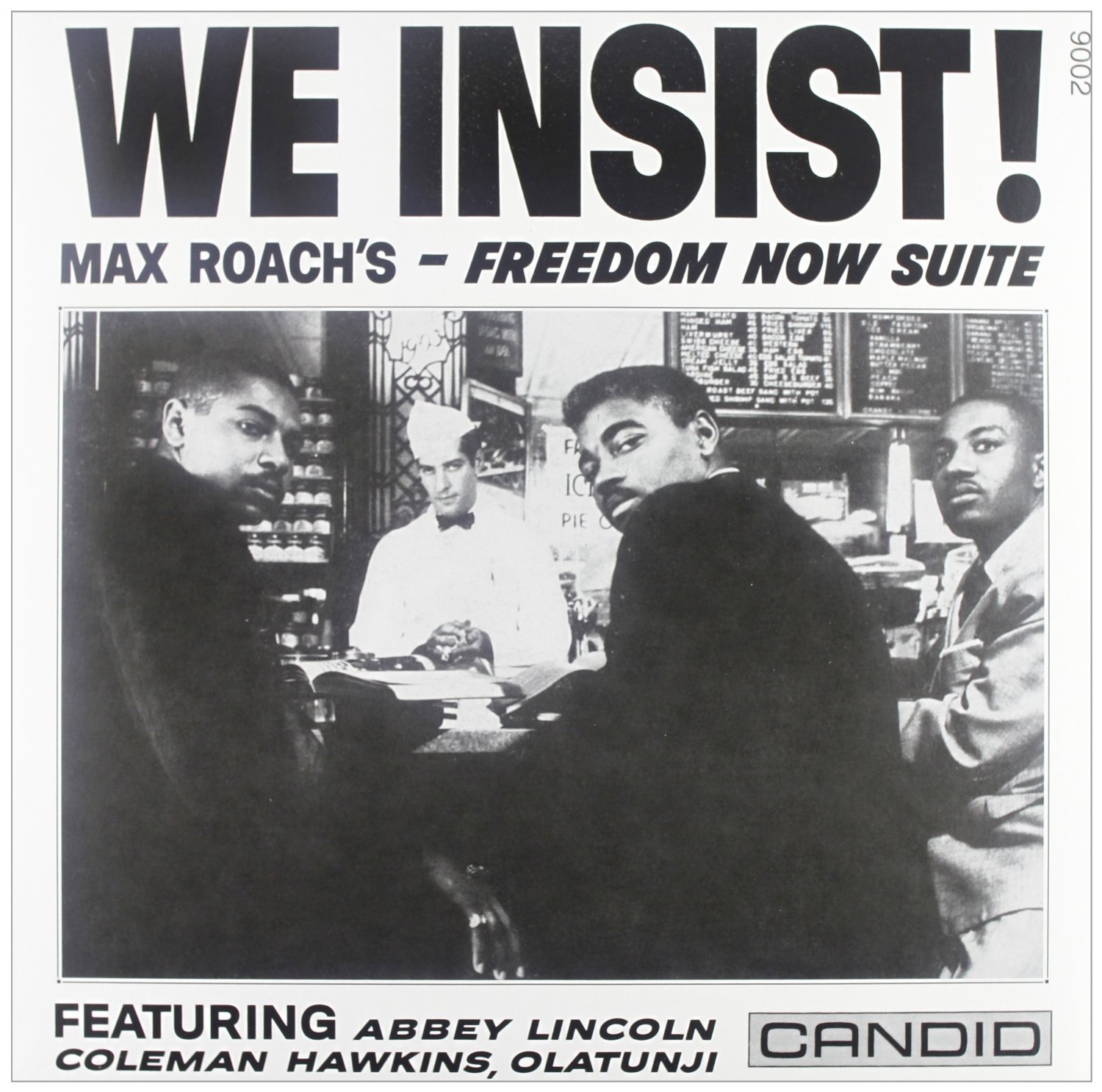

“You Don’t Know What Love Is,” Lee Konitz with Joe Henderson, The Lee Konitz Duets, 1967.

The first time I heard this tune, and nearly every time since, there’s some point or other at which I seem to forget that I’m listening and the saxophones sort of take over my consciousness. I lose track of who’s playing what but one thing remains certain: Mr. Konitz, outside this duet, never has this effect on me. Mr. Henderson, on the other hand, has this effect on me frequently, and at every phase of his career.

Like many players in the late-60s and early-70s, Henderson seized an opportunity to stretch out further than he had even in the previous several years. His move to Milestone Records6 brought larger, funkier bands into the picture. Henderson was equally at home in this environment as he had been in every other7, and the aggressive tones he’d worked out during his Blue Note years simply erupted. Though it also appeared in the Milestone box and on Soul Jazz Records’ marvelous Freedom Rhythm & Sound: Revolutionary Jazz and the Civil Rights Movement 1963-82, this tune originally appeared on his Black Is the Color LP in 1972, and characterizes for me the kind of force Joe Henderson was capable of:

“Foregone Conclusion,” Joe Henderson, Black Is the Color, 1972.

This was not a live recording. What you’re hearing, in part, is Mr. Henderson on alto flute, soprano saxophone, percussion and, obviously, tenor saxophone. The groove is fierce. 8 Which goes to the point that you could pick up pretty much any one of his records from pretty much any point in his 40-year career and find something passionate, conscientious, and technically astonishing. His was an awesome career. He is missed.

Thanks and shouts to my friend, Michael Honch, who turned me on to Joe Henderson nearly 20 years ago.↩

e.g. John Coltrane, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Pharoah Sanders; the point was clear: either one was hip to Mr. Coltrane’s journey out and the men heading there with or behind him or one was not quite with it at all.↩

This is not a figurative statement. In addition to his sessions as a leader, Henderson played with Kenny Dorham, Horace Silver, Lee Morgan (on “The Sidewinder,” no less), Grant Green, and more.↩

There were seven in all, two of which featured Hill’s all-rhythm quartets (no horns or reeds – either piano/bass/bass/drums or piano/vibraphone/bass/drums), and two others which featured John Gilmore, a worthy subject of tenor saxophone pursuit in his own right. Mr. Hill, of course, is a whole other study altogether.↩

In 1966, Blue Note released Mode for Joe, which would be the last Henderson-led LP on that label until 1985’s State of the Tenor, a 2 disc live set recorded at the Village Vanguard.↩

His entire Milestone catalog was released as a box set in 1994.↩

Unlike some of his colleagues who more or less disappeared into an almost-visible haze of reefer, cocaine, and neverending sunsets under the increasingly warm, airless guidance of CTI Records.↩

Bassist, Adam Rizer, likened the physical effect of such stern grooves to whiplash. He was talking about the Budos Band but I experienced this phenomenon with this number on my ride home from work today.↩

Marty Ehrlich’s Dark Woods Ensemble, “Tribute,” Live Wood, 1997.

The Live Wood set was recorded over the course of a European tour in 1996. The line-up for this tour was Marty Ehrlich, winds; Erik Friedlander, cello; Mark Helias, bass. The group has elsewhere included percussion, guitar, and other instrumentation.

I first saw Ehrlich perform in Andrew Hill’s sextet at the Knitting Factory in 1998. It was among the best shows I’ve ever seen, in no small part because of Ehrlich’s versatility and range, to say nothing of his attention to the other musicians. He is a consummate performer: assertive & gracious to both audience & bandmates.

Other recommendations: Dark Woods Ensemble, Sojourn (Tzadik, 1999); Marty Ehrlich,News on the Rail (Palmetto, 2005); Andrew Hill, Dusk (Palmetto, 2000).

I listen to a fair amount of jazz but am not a jazz-geek in the regular sense of the term: I don’t pour over liner notes, I’m not very good at remembering titles, and I tend to think of records/groups/performances in terms of their leaders and drummers, regardless of who else appears. I’m drawn to jazz mostly because of how it feels to listen to jazz, and one of the best-feeling composers and performers I’ve come across, Andrew Hill, died in April.

Though best known for his adventurous Blue Note LPs recorded in the 1960s, Mr. Hill’s career was consistent and seamless, whatever label- or promotion-related difficulties he faced along the way. In the course of the last 40 years, he continuously sought new arrangements for the instruments in his groups (including, at times, human voices), new rhythmic variations, new harmonic interplay.

He was, in his way, without peers, bridging an often-felt gap between the genre’s freer and more conventional modes. He was and is as fine an entry into avant-garde music as I know of. His passing is a tragedy, to be sure, and no small loss to both the performing and listening communities.

“Hey, Hey,” Lift Every Voice, 1969.

“Mira,” Grass Roots, 1968.

“15 8,” Dusk, 2000.

Sun Ra Arkestra, “Nuclear War,” Freedom Rhythm & Sound, 2009 (Nuclear War, 1982).

I love clarinet. I think it’s primarily the tone — a bit thin compared to brass, rounder than double-reeds; ecstatic as opposed to joyous; instead of longing, despair and lonesomeness — which strikes me, more than most instruments, as being shaped precisely as it sounds.

The tune that brought clarinet to the front of my mind this week is “Pamela’s Holiday”, a bright, shimmering number. Summer music.

“Pamela’s Holiday,” Wendell Harrison & Mama’s Licking Stick Clarinet Ensemble, Rush & Hustle, 1994.

Some of you will recognize the brand of 6/8 at work here: I tend to think of it as the “My Favorite Things” feel established by John Coltrane’s quartet.1

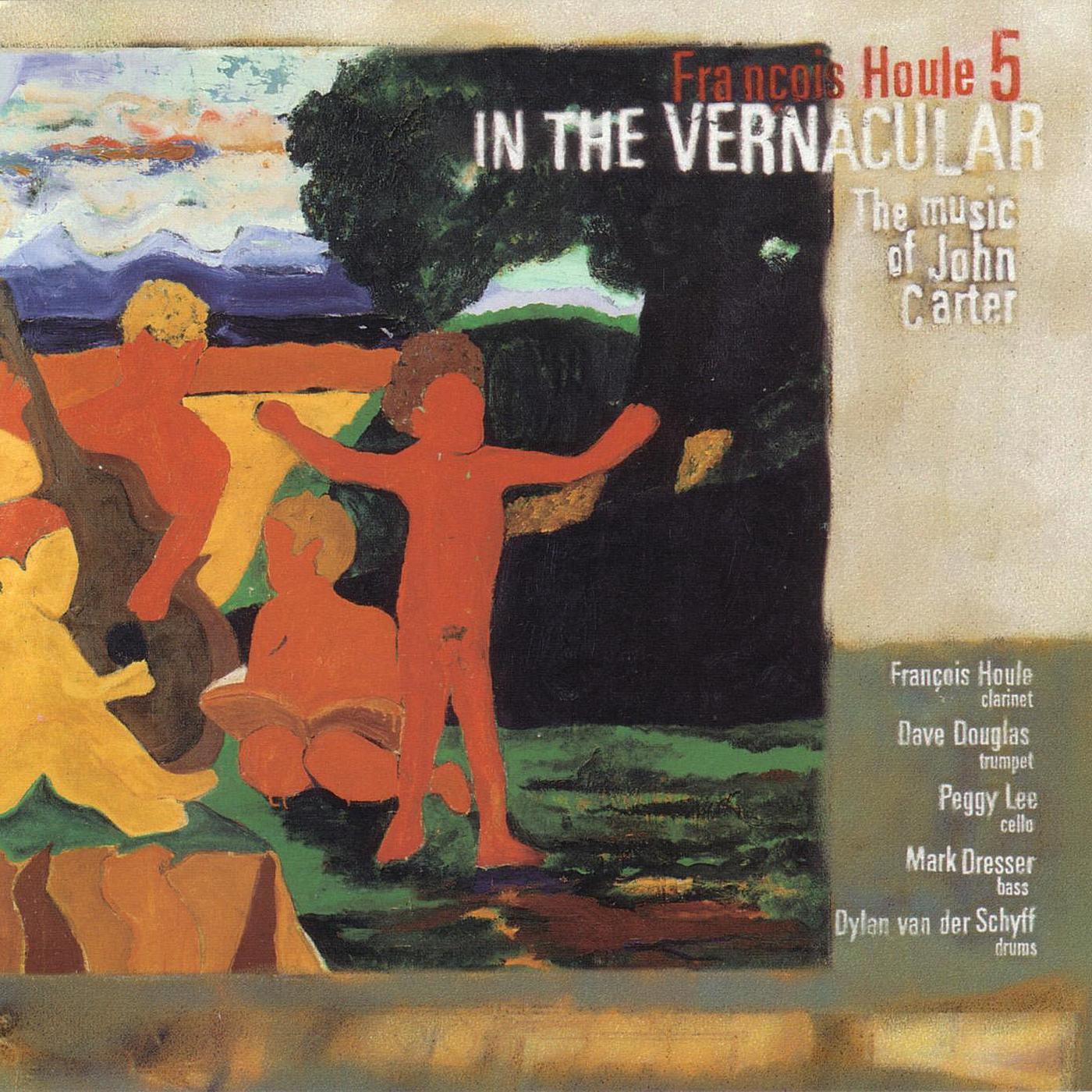

Another favorite clarinet performance of mine is from the François Houle 5’s In the Vernacular CD, a collection of compositons by John Carter.

“Morning Bell (prelude),” François Houle 5, In the Vernacular, 1998.

I’m not sure what to say about this piece except that it’s one of two records I’ve ever bought because I heard it playing in a record store. I had never heard anything like it before. Whatever avant-garde energies are at work, it is the attention to tone that compels the musicians.2

Which group, I might add, made a signature of that time signature. Paul Desmond’s innovative “Take Five,” performed by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, preceded the Coltrane Quartet number by two years but it was the latter’s understanding of this relatively long swing that brought some muscle to bear. The Harrison track seems to draw from both sides of the feel, buoyant and soaring, unafraid to assert itself when needed.↩

For what it’s worth, the other Houle work I know is far farther out than this set. F.H.’s devotion to Carter’s compositions is fierce, loving.↩

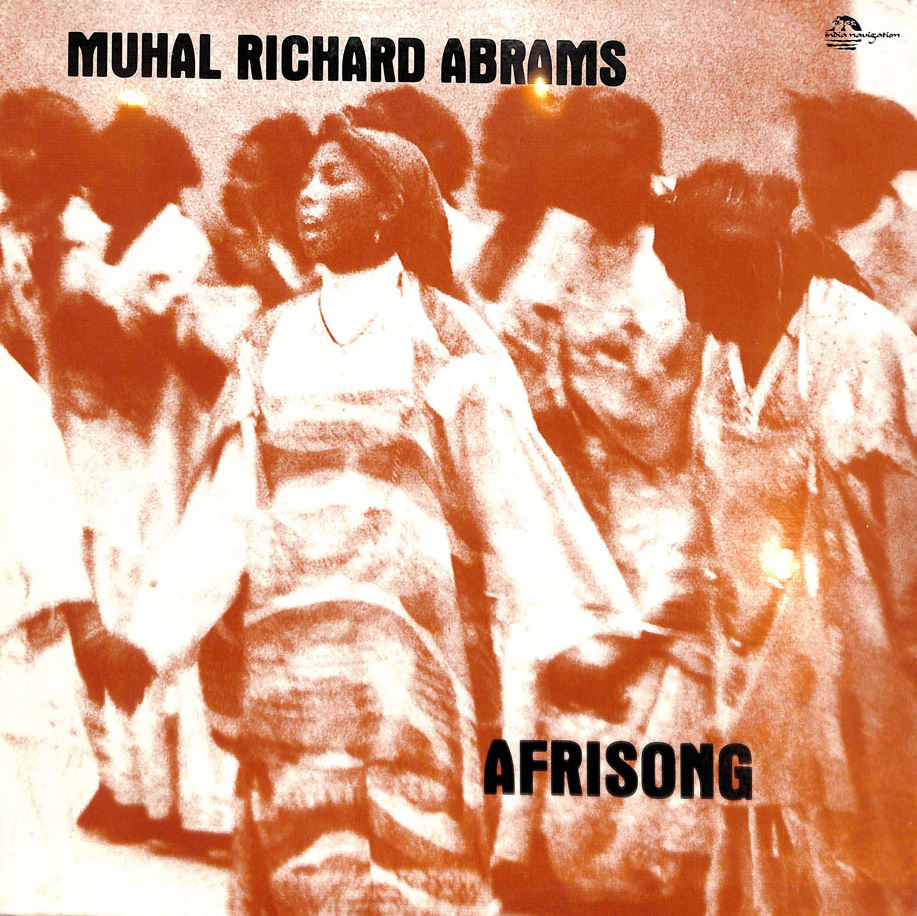

“Hymn to the East,” Muhal Richard Abrams, Afrisong, 1982.

I picked up Muhal Richard Abrams’ Afrisong LP yesterday, and though I was not familiar with this record, I liked the cover and have had good luck with other India Navigation titles in the past 1.

Frankly, I couldn’t be more pleased. Abrams’ playing here lands for me somewhere between McCoy Tyner and Keith Jarrett; that is, he appeals like the former in his chords/rhythms and the latter in his flight, for lack of a better term 2. Communicative and uplifting.

e.g. Arthur Blythe’s The Grip, Anthony Davis’ Lady of the Mirrors, and Cecil McBee’s Alternate Spaces, three of my favorite not-too-far-out recordings from the late 1970s and early 1980s.↩

I’m lying. I think flight is a terrific term and means, for these purposes, exactly what I trust it implies: his energy, his lift, his movement.↩

McCoy Tyner, “Vision,” Expansions, 1968.