Jamie Branch

A Passing Thought about Drumming

Drumming, at its best, poses a challenge to its collaborators in not only its tempos and time signatures but also in its spirit, its capacity to overwhelm or defer dynamics. All good drumming shares the common element of shepherding its ensembles.

Yomoko Noto Gitano, Solo Marimba

RIP Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre

— Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, 1936-2013

Closeness: The Untold Story of Kalaparusha

Inspiration: Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians

47 years ago today, a group of musicians gathered in Chicago, IL to form an organization whose aim was to support music that fell outside the parameters of conventional practice, culture, and exhibition. The following week, the group came to be known by the name it has had since that day: the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians, or the AACM for short.1

The AACM is still very much alive in Chicago (less so, it appears, in New York), still hosting concerts, students, resident musicians and groups, still very much a part of its local and broader communities. Further, the music it supports remains as diverse as ever, the depth of its commitment to what has been variously called Original Music, Creative Music (my personal favorite), and finally Great Black Music, unwavering.

Their work has been deeply inspiring to me the last few months, a reminder that one’s obligation as an artist is to try new things, however contrary they might at first be to one’s own practice; that one’s conscience is as good a guide as one is likely to find; that one should always strive for growth, both personally and with one’s instrument and group; and that music is a force of tremendous energy in all events.2

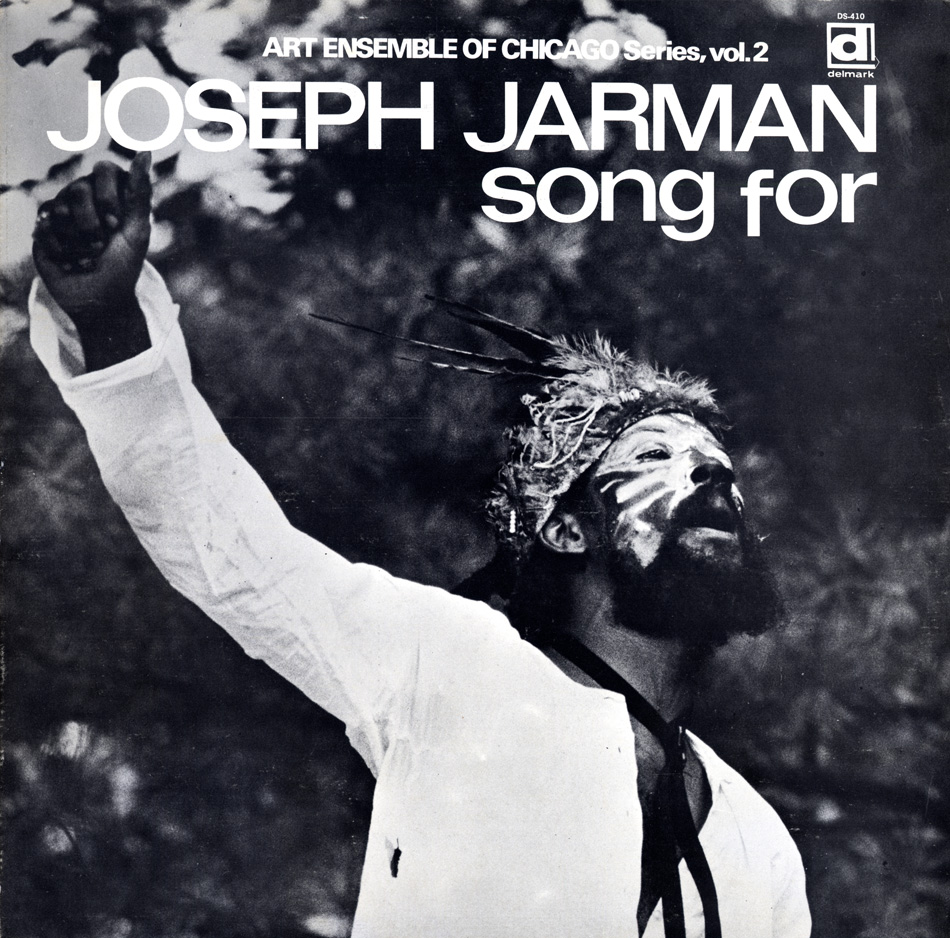

The roster of musicians who have been affiliated with the AACM through the years is nothing short of astonishing: Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Joseph Jarman, Leroy Jenkins, Roscoe Mitchell, Lester Bowie, Tomeka Reid, and countless others.

But because this is an anniversary, I’ll stick to the earliest AACM-affiliated recording I have on hand.

Enjoy.

Joseph Jarman, “Little Fox Run,” Song For, 1966.

For those interested in learning more, the AACM’s story is well-told in George Lewis’ remarkable A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music, a history of Chicago, jazz, African-American diaspora, and the struggle against the cultural status quo.↩

I feel a relative affinity between the kind of social and cultural disruptions my peers and I have sought through our own independent music scene and those carried out by the AACM. Like so much else, however, this idea requires elaboration and amplification better suited to another post.↩

From my old blog, February, 2007: On Selling Out, Sort Of

My experience as an artist is more or less divided into two spheres: on the one hand, I’m a musician, a practice which has always involved public performance and the explicit realization of a community. On the other hand, I’m a poet, a practice which has been, until the last year or so, an almost entirely private practice, one I shared with a handful of people, whose publication was limited to a couple of poems published several years ago (including, as it happens, the same poem twice). By and large, the two spheres remain separate, though, decreasingly so. I have tried to model my life as a poet on what I learned in the Rochester, NY and DC punk scenes from roughly 1989-2000: that artists, regardless of their art, carry with them a responsibility to the world in which they create and exhibit their work (it is, after all, created and exhibited in the same world).

The Jim Saah photograph above is from a Jawbox show at the Black Cat in DC; I think the year was 1994 and it might have even been the show advertised in the poster next to it. I have kept a print of the photograph on my refrigerator since that time to remind me of several things, chief among which has become the best-integrated art/politics scene in which I have been an active member. It was the reason I moved back to the area in 1991, and found it to be an invigorating and inspiring time and place to be as both writer and musician (I had, when I left Rochester, decided to give up music entirely, in favor of literature; thankfully my mind was changed nine months later when I joined Jawbox). There was a near-constant air of protest, of seeking out materials and economies that abandoned convention in favor of defiant humanism and concern for essentially leftist values. This took place mostly among bands and show-attendees, who were gathering anyway for music and new ideas. There were frequent benefit shows, protests, and a network of people around the world whose contact with each other depended on touring bands. The link was inherently political: we were doing our thing, not the mainstream thing. It worked, too.

By 1994, several of us (by which I mean bands) had signed to major labels, in hopes, variously, of reaching larger audiences, or at the very least, having more time and money with which to make records. I think Jawbox was more concerned with writing better songs than we were with fame. The jump to the majors allowed us to practice more, tour more, and record under better circumstances.

The ramifications were obvious enough then as now: we were selling out. For my part — I can’t speak for J., Bill, or Kim — I’ve always thought of it as cashing in, though there wasn’t really much cash and I’m not certain that the distinction even matters anymore. For what it’s worth, I didn’t feel like we were wrecking anything by signing to Atlantic; that is, the decision was ours, the consequences were ours, and it didn’t reflect on any other bands, labels, or fans. I was wrong.

The scene from which we’d come felt, in some circles, betrayed, and the mainstream rarely has the patience required for unconventional art. We were ignored by our label within nine months of our first release and completely pushed aside within a year. Our story is not at all unusual except perhaps for the degree to which we continued to practice a DIY-based method, regardless of being on a major label. We knew what we were getting ourselves into (most of the time). I don’t know that this recounting requires much elaboration at this late date so I’ll just say that if I was in that situation today, I’d probably handle it differently, though this remark is qualified by knowing that the circumstances that made Jawbox possible at all no longer exist for me.

In the end, I can’t say I regret our deal with Atlantic. Kim and Bill even bought our tapes back from the label and are planning to re-release both For Your Own Special Sweetheart and Jawbox online. The fact remains that we made our most challenging music under those conditions, and my experience in that band has positively served my consciousness as much as anything else I’ve done, before or since.