I began playing a drum set when I was 10 and showed promise and aptitude for the instrument from the start. It didn’t take long for music to become a significant part of both my identity and my worldview. During an especially unhappy period of time in Fairfax, VA when I was 12-13, drumming and music came to be my only source of social capital or interaction. I was fortunate to find, or be found in shop class by, a similarly disenchanted boy, one of extraordinary musical skill named Kevin who needed a drummer. What 12 year-old approaches another and says he “needs a drummer?” Prior to this he had only spoken to me twice, the first time he said “Cool bandana,” which was of course not true though I believe he thought it was. The second time, looking over my shoulder as I pored over the pages of the fall 1981 Pearl Drums catalog, he pointed at a black five-piece kit and said, “I have that one.” So he needed a drummer. He had my dream drum set and no one to play it while he played keyboards or guitar. I have counted Kevin McKendree among my dearest friends since that time. His talent persists, too: he is among the most intuitive and supportive musicians I have ever known. A true inspiration.

I bring all of this up because it taught me that playing music could be the entirety of a life, or close to it, its whole flow, in and out, as Peter Gabriel has come to say, delivering me from all manner of pain and confusion and loneliness to a world of people working together to make themselves and others feel good or better. And not only did I encounter this sensibility as a player, I came to internalize it as a listener. And a year later, I saw the “Games Without Frontiers” video for the first time. Three years after that, still imbued with this sense of music I could neither quite grasp nor articulate, I heard So for the first time, a record that would change me forever, become a baseline of what music, any music, can aspire to in its ability to self-generate its moment and environment, its own container, its own prophecy and destiny. It was very heavy stuff for my young mind.

I didn’t know this at the time, but it was a sort of big bang in my consciousness. Or if I intuited it, it wasn’t something I could deal with yet. The missing ingredient, as it happened, came in 1988 when I joined or fell into the punk scene.

It turns out that many young punks in the mid- and late-1980’s met because they had gone to rehab. I won’t go into it any further than that, but I was no exception to this trend, even if I seemed to get there (to punk, not to rehab) a few years later than my friends. This was fine, though, as they were there to shepherd me along. I came to understood punk to be much more of a mindset than a style, and it was through this mindset that I recognized the full achievement of So. The link was that one’s commitment to one’s art or even one’s self at all, could be unfettered by what one used to do or be. One could decide to change and, with varying degrees of difficulty, do so. If I wanted to be punk, I’d have to decide what that meant or looked like.

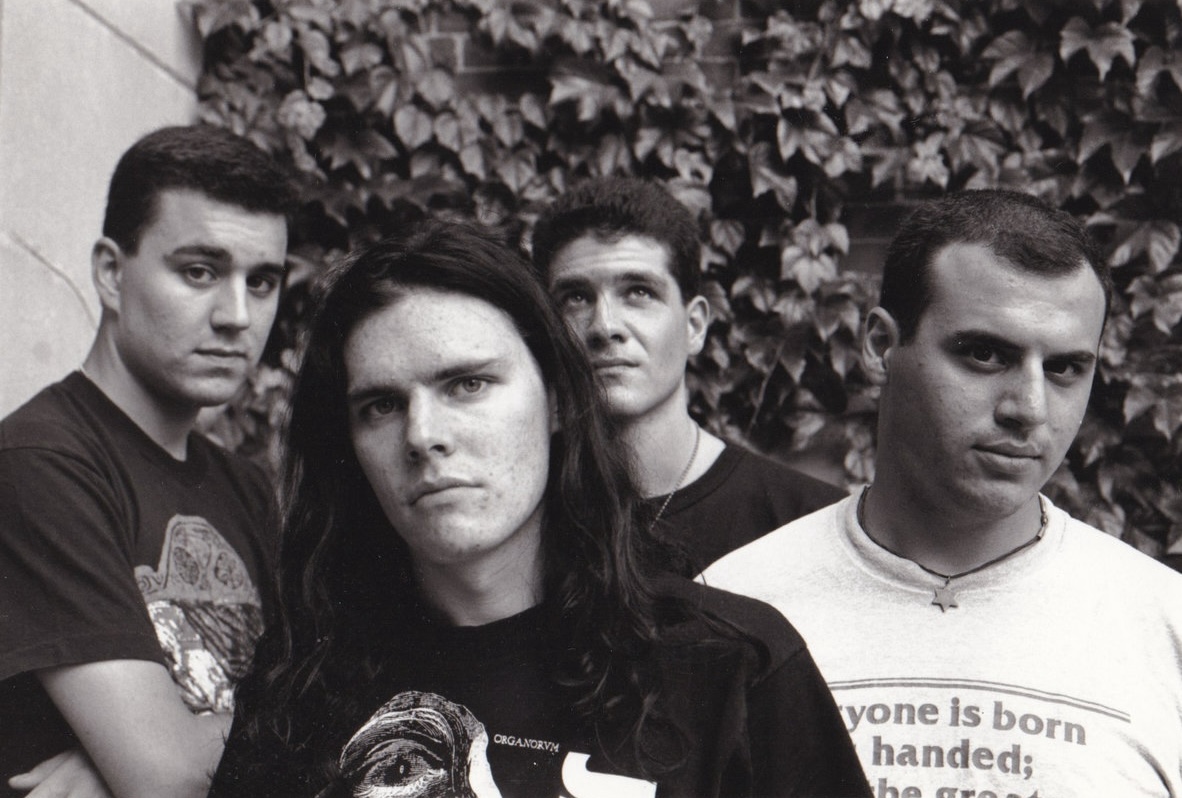

If I wanted to play punk music, the same principle would apply. There was room in the scene to drum in a way that included whatever I brought to the group. It was much more open than I understood other music to be and this sensibility gave rise to the drumming I would develop a few years later when, after a brief hiatus from playing altogether, I joined Jawbox. All of which brings us to my playing on the record for which I am usually best known, For Your Own Special Sweetheart.